It Comes Down to Empathy

by Ellen Wanamaker

Two times recently I’ve had that bittersweet experience of reading a book I couldn’t bear to finish. Of course I finished both, and have been raving about them ever since.

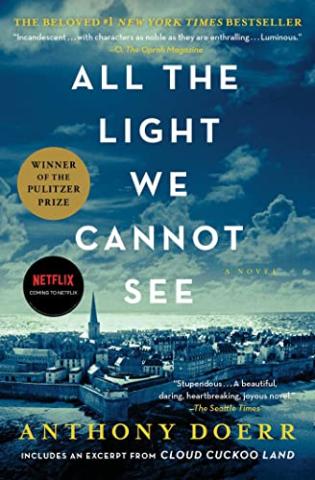

A few years ago I read Anthony Doerr’s “All the Light You Cannot See.” That story, set in Nazi-occupied France, gave us two characters so real I felt like I’d been personally introduced. The story featured blind teenager Marie-Laure, whose father carved a replica of their walled city so she could learn the layout by feel, and Werner, forced into the Nazi army as a teen.

I eagerly anticipated Doerr’s new novel, “Cloud Cuckoo Land”, and was equally thrilled with the depth of the characters. Doerr has a gift for intimate detail that make you nod and understand each character’s worldview and motivations. “Cloud Cuckoo Land” intertwines the lives of five people across hundreds of years, both on earth and beyond. There’s Konstance, 14 years old and living on an inter-generational spaceship. Seymour, a troubled boy in present-day Idaho who loves nature and goes to extremes to protect it. Zeno, an 80-year-old who is trying to decipher and revitalize an ancient Greek story. And two young people in fifteenth-century Constantinople - Anna and Omeir - whose lives collide during the siege of that walled city.

Cloud Cuckoo Land is a book about all these dreamers who have, as a connection, a love for stories, libraries and librarians (ha ha!). All of them are enraptured by the almost-forgotten story of Aethon, who longs to be turned into a bird so that he can fly to a utopian paradise.

I appreciated Konstance’s curiosity as she “walked the earth” using a sci-fi version of virtual reality goggles. I rooted for Seymour as he befriended owls and battled developers in his Idaho town. I followed Zeno’s entire life, from orphan to soldier to scholar. I admired Anna’s bravery in walled Constantinople, risking her life by stealing old scrolls. And I fell in love with sensitive, intuitive Omeir, born with a cleft lip in a time and place where he was seen as a bad omen. Omeir’s connection with his beloved oxen, Tree and Moonlight, unwittingly snared him into a battle he had no interest in fighting.

Fighting battles is the theme of the second book I recently fell in love with. Miriam Toews’ “Fight Night” is set in modern-day Toronto and features a mother, daughter, and grandmother who have their fists up against obstacles in their present and past lives. Foul-mouthed nine-year-old Swiv narrates the novel as a letter to her absent father. She has been suspended from school, and spends her time ducking from her mother’s “scorched earth” anger, and tenderly caring for Grandma Elvira, who is both frail and indomitably alive and hilarious.

The narration of “Fight Night” is illogical and jumpy, and Swiv relays myriad conversations with little punctuation, oddly effective because it feels like a child’s natural thought process.

When asked why she always shouting, Swiv responds, “Grandma is hard of hearing and Mom is hard of listening so I have to yell all day long.” She’s very much a 9-year-old sometimes (grossed out when her mom and grandma talk about bodily functions) and preternaturally mature at other times (“… I was happy when she said the question was rhetorical which means I didn’t have to answer. I wished every question in the world was rhetorical.”) Grandma and Swiv eventually take an outlandish trip to California, where Swiv learns to drive (!) and gains insight into the family tragedies that shaped the love and dysfunction of their current situation.

I was chatting with my son recently about why we read fiction. What does it do for us? What do we gain? We talked about how it comes down to empathy. Even though these fictional characters aren’t real, they exist in my mind. I’m thankful for Doerr, who introduced me to Konstance, Seymour and Omeir. And I’m thrilled with Toews for creating Swiv and Elvira. Their lives are nothing like mine, but I understand what they’ve gone through and feel for them. That’s what good fiction does for us.